Artist Iain Stewart shares his therapeutic process of recording his days in sketchbooks.

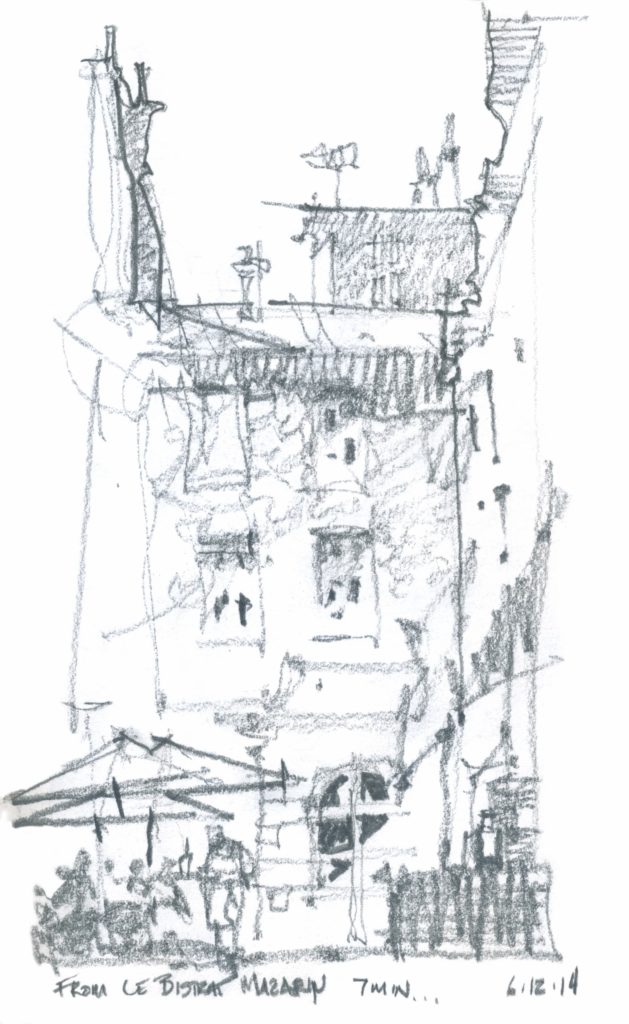

“I’ll tell you what,” starts my wife Noelle. “I bet you can’t sketch that view before I finish this glass of wine.” She gives me that mischievous grin of hers as she takes a sip. It’s June in Paris, and beads of condensation drip down the stem of the glass. I look at my unopened sketch bag. The odds aren’t good. I begin to stammer some excuse—but then I stop and grab my gear. “You’re on, babe.”

This article originally appeared in Watercolor Artist, June 2019 issue. Subscribe now so you don’t miss any great art instruction, inspiration, and articles like this one.

Seven minutes later, and just before the last half-ounce of chardonnay makes its final journey, I say “done,” and order myself a beer in triumph. It’s not my best work but, as it turns out, it’s one of my favorite simple sketches. Every time I see it, I’m transported to that exact moment in time and place, sharing a cool beverage with my wife in the back streets of the 5th arrondissement. It’s a memory I cherish.

Drawing Out Stories

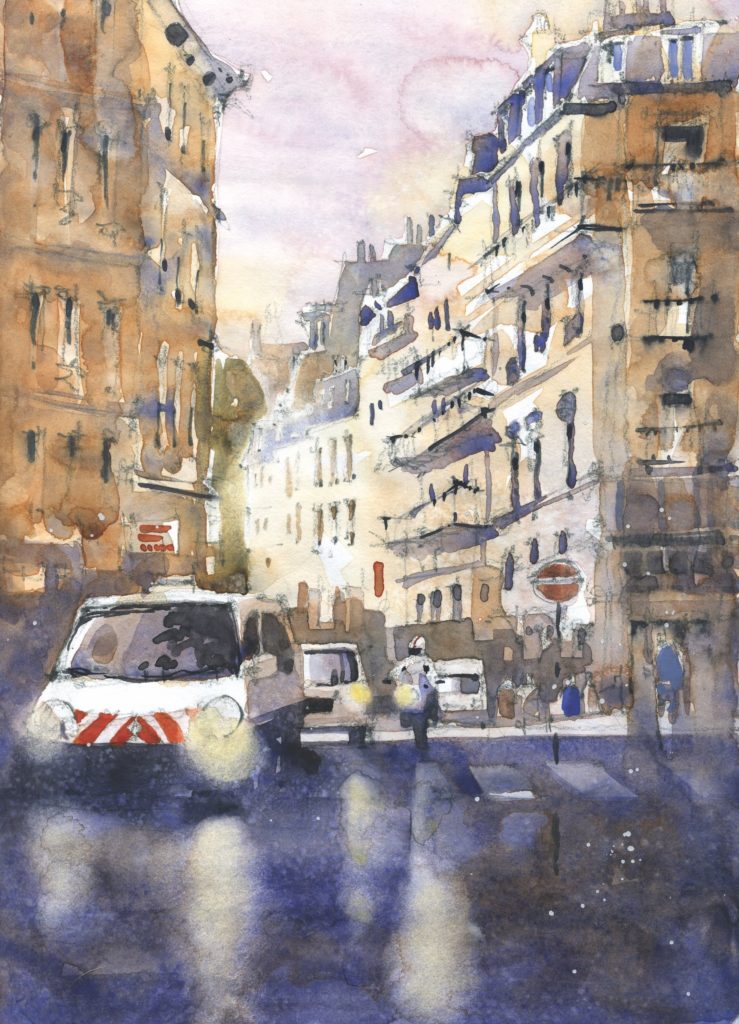

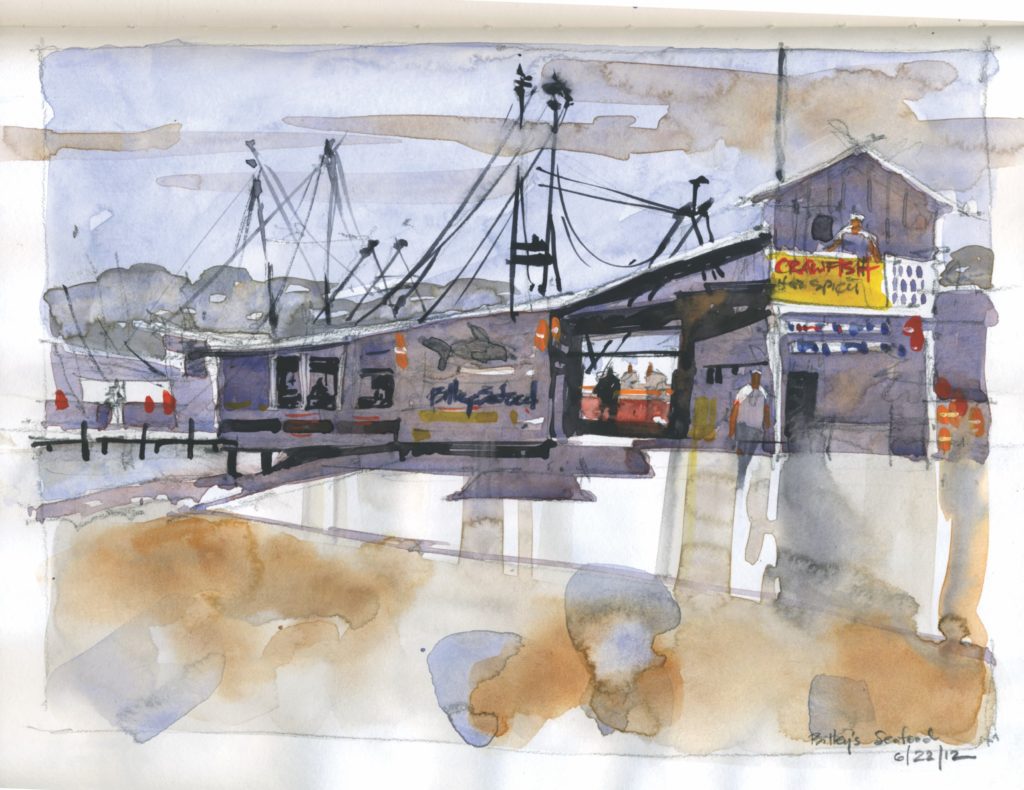

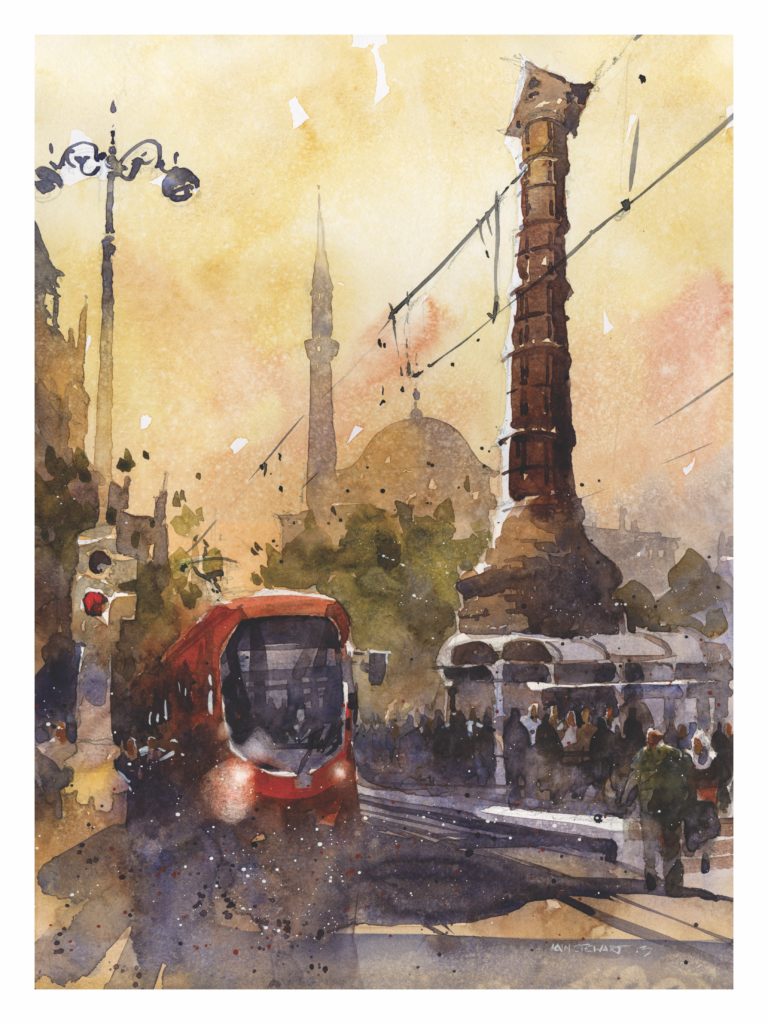

There are many more sketches of Paris, and there are sketches of other beautiful places, along with sketches of my backyard or various rural spots. They all have stories. I live my life in the present and remember it through my sketchbooks. Understanding why I find my sketchbooks so valuable, and using my persuasive powers to try and convince others to join me in this way of recording a life, is something in which I take great joy as an instructor.

One-Rule Sketching

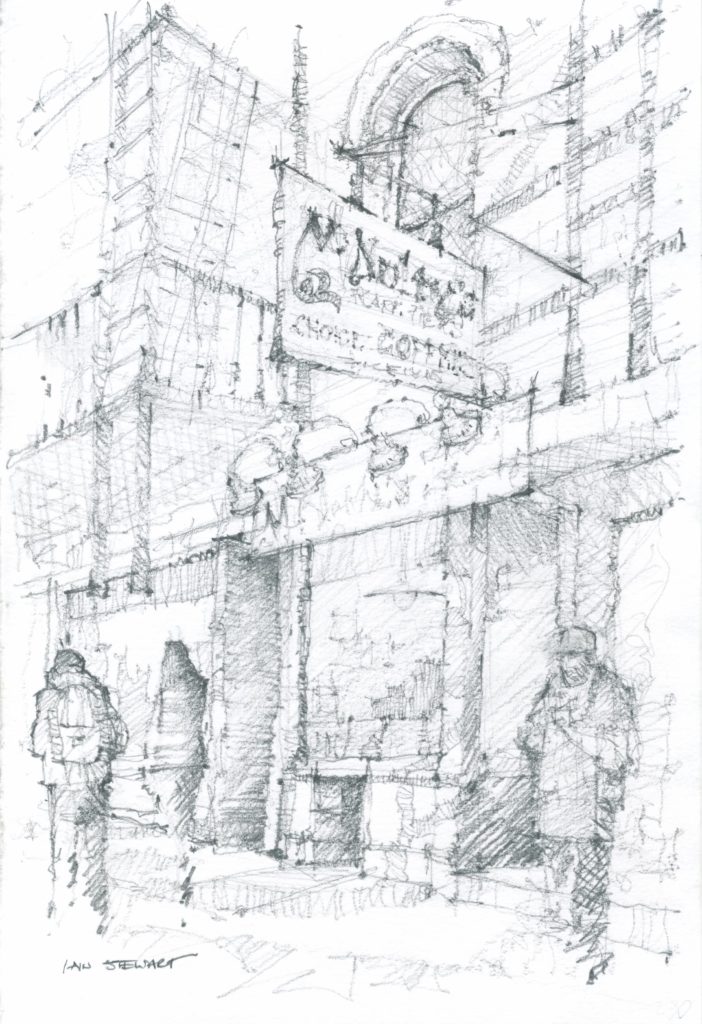

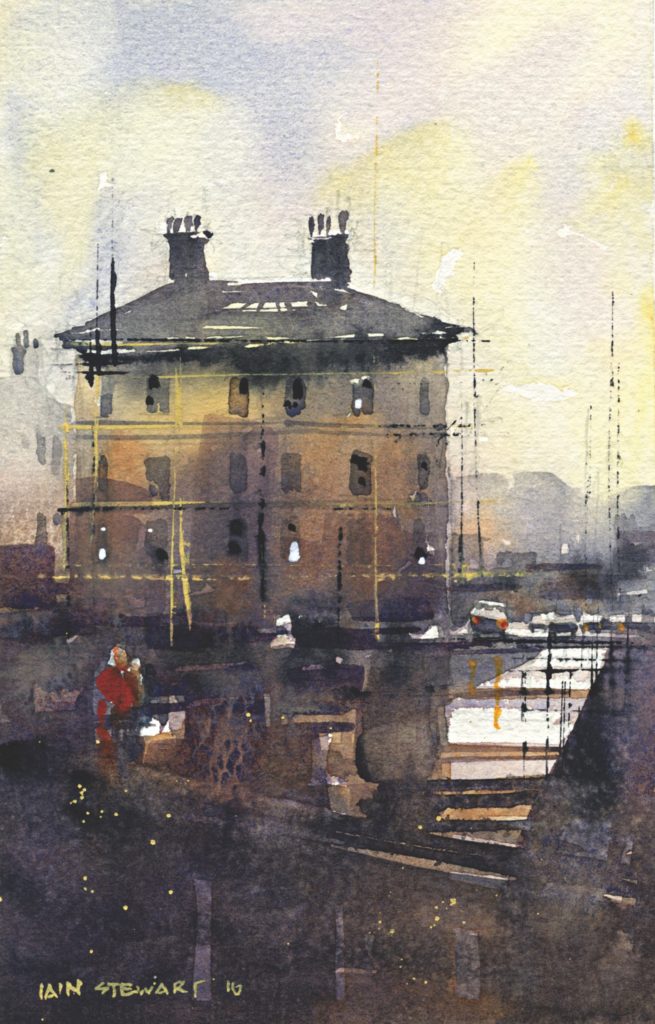

Simply put, a sketch is a quick expression of where you are—mentally or physically—rather than a verbal explanation. The sketchbook is my place of joy, observation, solace and exploration. The more I work in it, the more my studio painting loosens up. Those who have painted with me before will understand firsthand how much I believe the sketchbook to be the perfect instrument for allowing creative instincts to flourish. It’s one of the best tools to improve your watercolors. I just have one rule: Never tear out a page. Even the simple sketches you believe to be poor have stories to tell.

Lighten Up

In June of last year, I took a group to Italy. From the very first demo, I worked primarily in my sketchbook, stressing the ease with which an artist can carry the setup for an entire day of painting and the number of images one can capture in a short time. A sketch doesn’t have the added baggage of being made for the purpose of framing or for sending to some juror to ponder its merits. You choose with whom and when you share your sketches. Too often I see artists disappointed when they try to take on too much during travel. I know. I’ve been there. You haul your easel and your kit all over creation, carefully tape down the paper, study your subject and then everything goes south.

Don’t try to bring your studio with you. I believe a better way to enjoy travel-painting is with less stuff and more exploration. It’s amazing how much of a city you can record with just a book, a couple of pencils, a travel palette and three brushes. A lightweight setup allows you to go much longer and with much more comfort. And this will allow you to collect more memories.

Letting Loose with Simple Sketches

I find the surest way to ruin a painting is to allow it to become precious before it deserves even the slightest accolade. Keeping a sketchbook allows you to begin to shed those preconceived ideas of what your work on-site should look like. Spend 15 minutes warming up with little vignettes, and then begin to explore where you are in more detail.

The object of sketching a place isn’t the outcome but the experience of sitting still amid the rush of tourists. Separate yourself from that crowd and become a part of where you are. Enjoy the aromas of a nearby restaurant, and the sounds of a new city or a new language. After a bit of time, you forget the need to create a masterpiece. It’s just a piece of paper in a book. It’s just a pencil. What have you got to lose? You get to know “place” on a much deeper level, and that practice in itself begins to instill a confidence that will serve you better than any other skill I can think of.

Warm Up Your Drawing Muscles

Like any other form of creativity, it’s important to warm up. You need to loosen your muscles, relax and get into your own private zone. It’s like the cacophony of the symphony as its musicians practice scales or like the athlete stretching before a match. These stretches are necessary for them to perform at peak level. Why should an artist have a different set of rules? Sketching is your physical and mental stretching. If you ever see me at an easel, I’ll typically do a few simple sketches before I begin work on the main painting. Quite often, these little sketches are more interesting to me than the finished painting.

Sketch Your Own Reality

On-site, your field of view is as far as you can turn your head. When you begin to design a sketch, that field narrows significantly. I might borrow the odd chimney or change the flow of traffic to suit my design. Feel free to shift elements around. Decide what the story is and then begin the task of throwing out anything that steals from it. Never let reality get in the way of a good painting. And never let a drawn line tell you where to put your brush. There are two drawings in every painting. The first is done with a pencil; the second, the one that everyone sees, is done with the brush.

Sketchbook Sanctuary

My kit is simple: a comfortable bag with a place for a water bottle and the necessities I keep packed and ready at all times. Gathering gear wastes time, and if you can’t find your water container, you may have a longing look at the couch and decide it’s a bit inclement for venturing outside. Put sketchbooks in your car, your purse, your backpack or wherever you need. I typically have four or five going at once.

As an instructor, I only show my “public” sketchbook. My personal one is where I write, as well. Those thoughts and memories are mine, and I keep them close. A good sketchbook is your sanctuary. Treat it as such. I have books going back to 1989 when I began studying architecture, and can revisit them and transport myself to age 21 or 35 or yesterday.

Even the most mundane setting provides an incredible amount of subjects to draw and paint. You only need to learn to see it, which requires practice. The journey is the process. The reward is what you make of it.

Drawing Time

In the rush of social networking and the 24-hour news cycle, I find the most peaceful way to approach the start of the day is to stay away from screens for as long as possible. Try it. Take 30 minutes with your coffee and draw. Choose anything on your table, look out the window or, better yet, go outside and give yourself some sketchbook time. A minute or two with your sketchbook will calm you in ways that might surprise you.

Lastly, let me leave you with this thought. The idea that simple sketches are somehow less important or too “rough” compared to more finished pieces is simply untrue. There’s an honesty to a sketch that’s rarely transferred to a studio piece. Of course, each is important in its own right, and they work symbiotically together, but for today, work on the sketch. Grab a sketchbook and go outside. I know I will.

About the Artist

Iain Stewart (stewartwatercolors.com) is an artist and illustrator, and a signature member of both the American and National Watercolor Societies. His work has received many awards, domestically and abroad, and he’s a sought-after workshop instructor and juror. For more great instruction from Stewart, check out his best-selling video series, From Photos to Fantastic, where he breaks down his techniques for Painting Watercolor Cityscapes, Painting Watercolor Seascapes and Painting Watercolor Landscapes.

This article originally appeared in Watercolor Artist, June 2019 issue. Check out the rest of the issue for more great painting techniques and inspiration!